As an impressionable lad who spent his days amidst stacks of old Motor Sport magazines, and his evenings buried in Doug Nye’s biblical tome on Cooper Cars (yup, they were heady days) the discovery that back in ’66 a guy named Frankenheimer had made a three-hour epic about Formula 1 racing was pretty exciting. From the day I saw it Grand Prix became my favourite film, and I watched it, or part of it, practically every day, memorising every line of dialogue, every gear change and even every continuity error. But more importantly than that, I learned the technique of capturing speed on film, how a director can perfectly harness the technology at his disposal, placing his audience at the very heart of an exciting and inherently cinematic pursuit, without resorting to the smoke and mirrors of a shaky camera and frenzied jump cutting.

Sadly nobody involved in the production of Rush appears to have reached the same conclusion, and though the resultant film might capture the sound and fury of a racing car unlike any other, what it fails to capture is the speed or skill of Grand Prix racing, in part because it lacks what might be considered a true racing sequence. Where Grand Prix utilises the film medium to its fullest extent in the pursuit of visceral realism, Rush misdirects its audience with a series of heavily edited sensory assaults, none of which lasts long enough to generate any tension from the racing itself. Journalist Simon Taylor, who actually commentated on the ’76 Japanese Grand Prix, reprises his duties here, adding what narrative there is to the images flashing before our eyes, and without him it must be said that even a fan like myself wouldn’t really know what was going on.

Beneath its hyperactive visuals though, Rush is a relatively straightforward biopic, delivering a quick précis of two careers, and exploiting the rivals’ famous differences of personality for ease of storytelling, whilst never really pausing to explore either character. The lead performances – especially that of Daniel Brühl – are uniformly excellent, but I can’t help feeling that the opportunity to explore two genuinely nuanced characters was missed. In reality, as I understand it, Hunt and Lauda were friends, not the best of friends perhaps, but that they remained on good terms at all through a year of such intense competition and adversity is incredible and surely makes the nature of such a relationship worthy of exploration. The protagonists of Rush however display few subtleties, each man having been reduced to his most basic characteristics: the ambitious Lauda with a brittle façade of ruthlessness, whose greatest fear is to find happiness and lose his competitive edge; and Hunt the swaggering, seemingly fearless bon vivant, living for the moment, yet famously prone to tension-induced vomiting before races and whose excesses obviously mask self-doubt.

Perhaps the issue for me is that screenwriter Peter Morgan attempts to cover too much ground, engineering events for the purposes of characterisation, rather than allowing them to be revealed through the extraordinary circumstances as they actually occurred. And it’s very much a two-man show, with Lauda’s wife Marlene popping up to humanise him a little, the supporting cast otherwise having to act like caricatures, especially the other drivers who are portrayed as a bunch of mop-topped half- wits, only Clay Reggazoni being given anything approaching a character – that of a lazy womaniser – though it’s clear he was featured only for expositional purposes.

I must apologise if this review sounds overly harsh, for there is much to like and be admired in Rush, not least Ron Howard’s energetic directorial style, which somehow feels appropriate given the film’s independent roots, lending the story both an air of immediacy and disguising the constant requirement for historical exposition. Anthony Dod Mantle’s cinematography also warrants mention, his innovative use of Indiecam cameras mounted inside crash helmets and on the cars is genuinely striking, whilst his colour palette creates an unmistakably seventies atmosphere, without resorting to the muddy shades of brown we’d usually associate with films of the era.

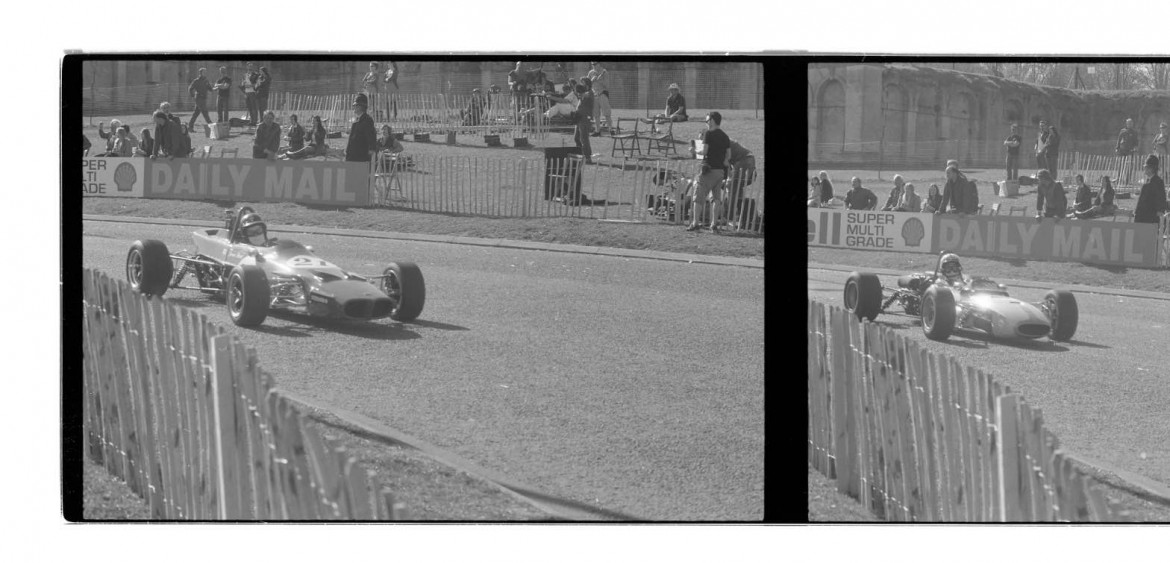

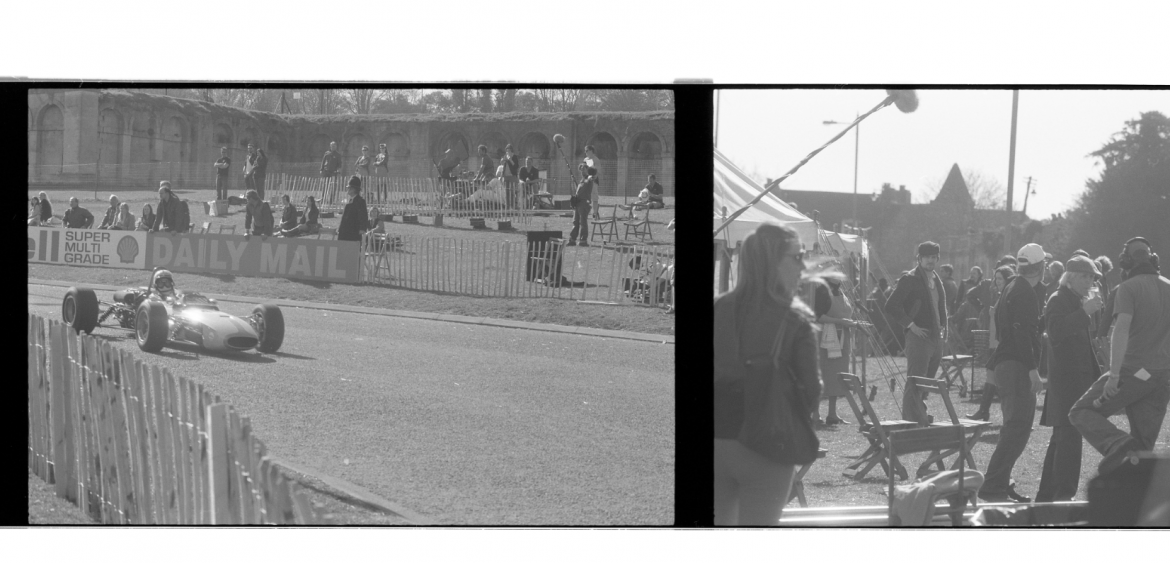

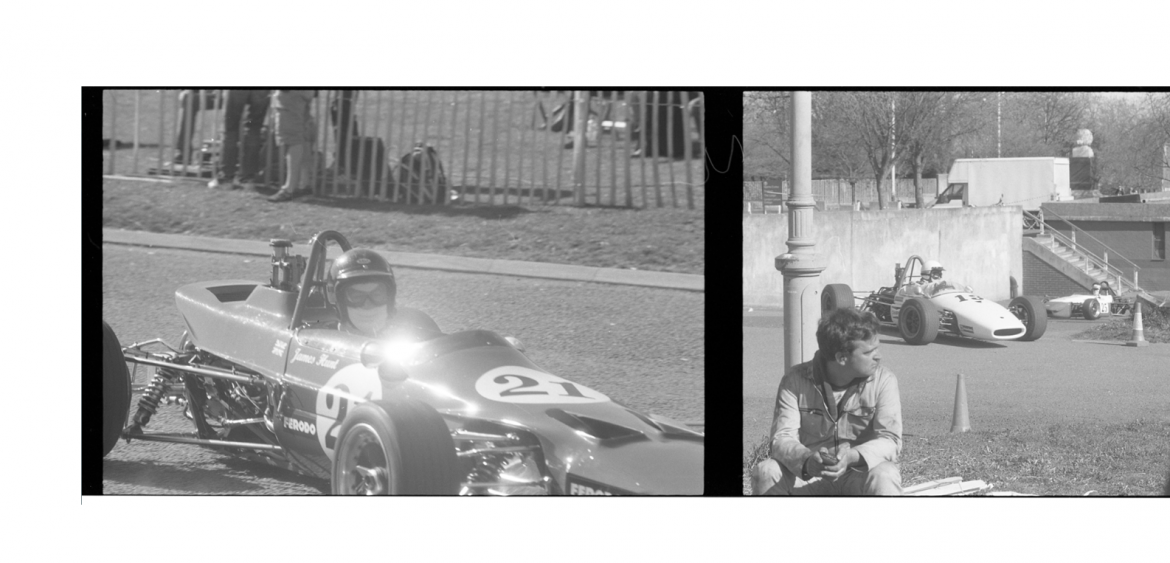

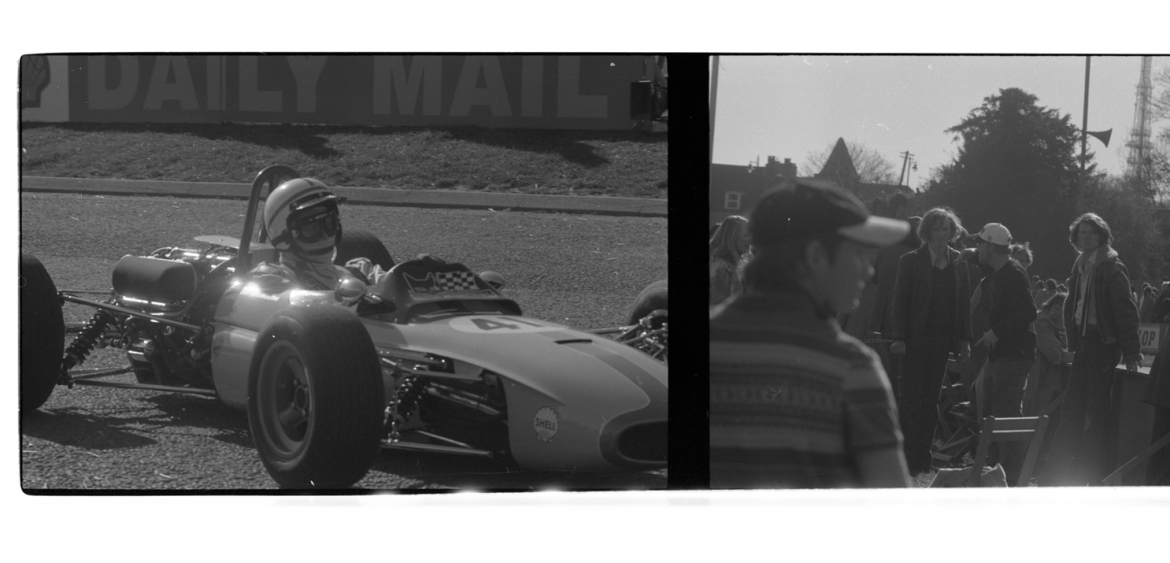

In spite of my reservations, it’s a pleasure to have had the opportunity to write about a new film set in the world of Formula 1 and the factual inaccuracies one might recognise as an enthusiast are ultimately of little concern, for the average cinemagoer wants only entertainment, not a lecture on tyre wear. The sights and sounds of F1 seventies-style will surely be enough to enthral audiences, many of whom will be experiencing them for the first time, and in the end, as John Surtees said to me at Goodwood, perhaps it’ll inspire a few youngsters to get involved in the real thing, which I guess is what Frankenheimer’s film did for me.

First published on Discoveryuk.com